Some things are just indecent. Some might be so indecent that we want judges to use the law to prevent the harm, outrage, and disgust they provoke. Free speech is not an absolute right; as the anecdotal example always goes: you can speak freely but you can’t yell fire in a crowded theater.

But no matter how indecent, inflammatory, or dangerous something is we don’t want judges to bend laws that were intended to regulate other activities, like the rights of creators to their creations, in order to fudge a quick fix. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what the Ninth Circuit in Garcia v. Google just did: censor an online video by taking an absurd turn in copyright law.

That may not be what the court intended to do, and copyright authorship questions can be notoriously complicated—just ask Spike Lee. But still, the practical effect of the ruling will be to chip away at our first amendment freedom of speech, at the vibrancy of our creative communities, and at the viability of the valuable services that deliver content online.

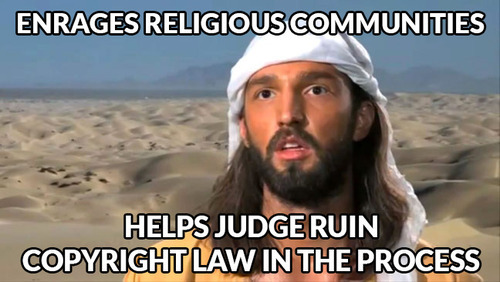

The video that started this is Innocence of Muslims, a deliberately inflammatory, assuredly unpleasant, and strikingly talentless video that popped up about two years ago. If you haven’t seen it, don’t. Even putting aside the riots it caused across the world, it’s just amazingly bad, aneurysm-inducing filmmaking.

Now, other bloggers have done a fantastic job parsing the precise absurdities of the court’s ruling but if you’re looking for the tl;dr takeaway, here it is:

The court allowed an actor that appears in the video for a few seconds the right, as in copyright, to immediately stop the film’s distribution, and forced Google’s Youtube to find and take-down every copy uploaded to its servers.

All this, despite the fact that normally the actor’s appearance would have been:

- treated as not copyrightable (because the short appearance lacks the requisite creativity or is not “fixed” until the final product is edited by the filmmaker), OR

- treated as a “work for hire” (you did this for the filmmaker who hired you so he/she owns the copyright) OR

- treated as a work for which an implied license was granted (the norm on the movie set is that if you contribute to a film you impliedly give permission to use your contribution).

Most worryingly, the court here isn’t ordering damages to the actor, it’s granting a preliminary injunction against distributors. This means a coercive prior restraint on speech across the Internet granted at least until the final merits of the case have been determined.

To make matters worse, the preliminary injunction was issued in secret to counsel at Google: they were ordered to take down all copies last week before the court’s opinion was released, and Google was gagged from discussing the order publically.

As a result,

- Filmmakers may suffer any number of copyright infringement claims from enterprising or disgruntled actors that contributed to their films, taxing creativity with legal uncertainty.

- Protections for free speech can be more easily circumscribed by finding someone to claim copyright infringement because of her participation, paltry though it may be, in a speech act.

- Content distributors, like YouTube, will be forced to monitor every bit of content uploaded to their servers in order to comply with inflexible, censorious injunctions. While this may be manageable for Google, which has sophisticated technical filters, it may not be manageable for smaller content distributors if judges took this case as license to censor online content more freely.

Whatever the legal analysis, this kind of decision undermines the moral legitimacy of copyright broadly — and thus public respect for it — by allowing legitimate copyright enforcement to be conflated with censorship.

Read more: Techdirt, Technology and Marketing Law Blog, EFF