“Just think about the children!” has always been the rallying cry of hyperactive regulators. Lately, the FTC claimed it was protecting children — well, actually, their parents — by second-guessing how Apple and Amazon designed their app stores. That prompted a scathing dissent from Commissioner Josh Wright, arguing that FTC enforcement action was “neither warranted nor in consumers’ best interest.”

The FTC’s been down this road before. In the 1970s, the FTC ran amuck with its vague power to declare practices unfair. The FTC chairman talked about regulating everything from funeral homes and labor practices to pollution. But Congress — a heavily Democratic Congress — wouldn’t have it. They reined in the agency, forcing it to narrow its conception of unfairness.

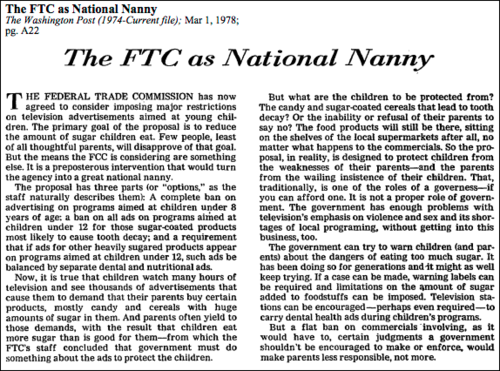

The straw that broke the camel’s back was the FTC’s attempt to ban advertising of sugared foods to children. This prompted a 1978 editorial from the The Washington Post, hardly a libertarian bastion, against the FTC’s overreach. That piece marked the beginning of the end of the FTC’s hyper-activist phase — and very nearly led Congress to close the agency for more than just the few days that served as the Commission’s punishment. Now that Congress is starting to look into how the FTC works again, we wanted to share the editorial:

Here’s the the original text:

The Federal Trade Commission has now agreed to consider imposing major restrictions on television advertisements aimed at young children. The primary goal of the proposal is to reduce the amount of sugar children eat. Few people, least of all thoughtful parents, will disapprove of that goal. But the means the FCC is considering are something else. It is a preposterous intervention that would turn the agency into a great national nanny.

The proposal has three parts (or “options,” as the staff naturally describes them): A complete ban on advertising on programs aimed at children under 8 years of age; a ban on all ads on programs aimed at children under 12 or those sugar-coated products most likely to cause tooth decay; and a requirement that if ads for other heavily sugared products appear on programs aimed at children under 12, such ads be balanced by separate dental and nutritional ads.

Now, it is true that children watch many hours and television and see thousands of advertisements that cause them to demand that their parents buy certain products, mostly candy and cereals with huge amounts of sugar in them. And parents often yield to those demands, with the result that children eat more sugar than is good for them–from which the FTC’s staff concluded that government must do something about the ads to protect the children.

But what are the children to be protected from? The candy and sugar-coated cereals that lead to tooth decay? Or the inability or refusal of their parents to say no? The food products will still be there, sitting on the shelves of the local supermarkets after all, no matter what happens to the commercials. So the proposal, in reality, is designed to protect children from the weaknesses of their parents–and the parents from the wailing insistence of their children. That, traditionally, is one of the roles of a governess–if you can afford one. It is not the proper role of government. The government has enough problems with television’s emphasis on violence and sex and its shortages of local programming, without getting into this business, too.

The government can try to warn children (and parents) about the dangers of eating too much sugar. It has been doing so for generations and it might as well keep trying. If a case can be made, warning labels can be required and limitations on the amount of sugar added to foodstuffs can be imposed. Television stations can be encouraged–perhaps even required–to carry dental health ads during children’s programs.

But a flat ban on commercials involving, as it would have to, certain judgements a government shouldn’t be encouraged to make or enforce, would make parents less responsible, not more.

For more on the FTC’s sordid history, read: “The FTC’s Use of Unfairness Authority: Its Rise, Fall, and Resurrection,” a paper by former FTC director J. Howard Beales

And for more on what to do about a runaway FTC, join us on Thursday, July 31 at the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company for a lunch and panel discussion on the important questions surrounding the FTC’s latest consumer protection enforcement actions. RSVP here.

You can also read the initial report of our “FTC: Technology & Reform” project launched in December.