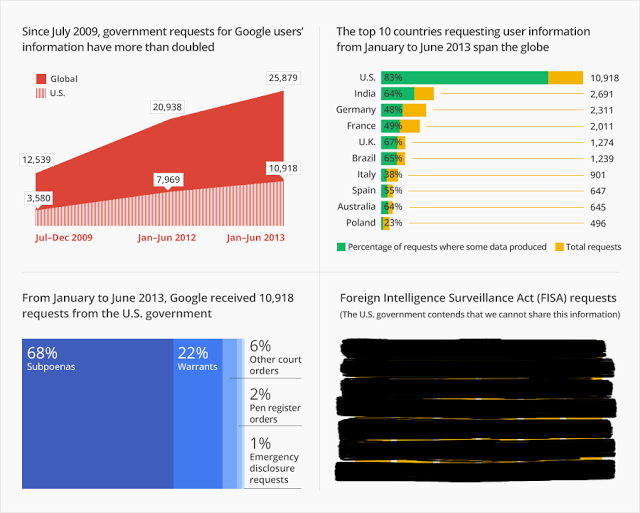

Yesterday, Google released its Transparency Report confirming what we already assumed: the government is demanding more personal data and using fewer formal requests. Since 2009, requests for Google user data by US law enforcement have tripled. But it gets worse:

In the first six months of 2013,

- 21,683 Google users had their data demanded.

- 17,402 Google users had their data demanded without a warrant

- 16,284 Google users had their data demanded with a subpoena that doesn’t require judge approval

That’s right, most of the requests for information were subpoenas, not warrants. The difference is crucial: whether law enforcement has to convince a judge that probable cause exists to believe a crime has been committed.

Existing federal law (the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986) is supposed to protect us. But ECPA is so outdated that law enforcement can access all kinds of private data never imaginable in 1986 with either warrants or two types of subpoena. One subpoena, the § 2703(d) order, essentially requires only relevance: a judge must find “specific and articulable facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe” that the requested information is “relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.” Think of § 2703(d) orders — or “D orders,“ as the cool kids in the courthouse call them — as Warrants Lite™.

But wait, there’s more! ECPA also allows law enforcement to use an Administrative Subpoena: same standard of relevance and specificity but guess who gets to “judge” those standards? The investigators themselves. Think of Admin Subpoenas as Warrants Extra-Lite DIY-Edition™.

So, again, Google is reporting that 16,284 users had their data requested by investigators who probably signed their own subpoenas. Put simply, in the first six months of 2013, due process got f#$%ed — a lot.

Google has been breaking down the type of request for only the last year. But a worrying trend is already visible: of all the users that had their data requested each year, more users had their data requested without judge approval in 2013 than in 2012 — both in relative and absolute terms. Investigators are becoming less likely to seek judge approval of their coercive demands for private data — directly contravening claims that they are obtaining warrants as required by the Sixth Circuit in its 2010 Warshak decision.

Content vs. Non-content

Now, Google says they don’t give out content information without a warrant, so any administrative subpoenas Google complied with must have been for non-content data. According to Google, for Gmail non-content data means:

- Subscriber registration information (e.g., name, account creation information, associated email addresses, phone number)

- Sign-in IP addresses and associated time stamps

But the real problem is that Google’s policy of not giving out content data without a warrant is just that: Google’s policy. The law, ECPA, doesn’t say they have to do that, or even that they can lawfully do that, and plenty of companies that don’t bear the motto “don’t be evil” – or just don’t have the in-house legal teams to fight the government, citing Warshak – may well be complying with warrantless requests for content information as lawful process under ECPA.

NSA vs. ECPA

TechFreedom’s been actively opposed to the NSA’s blanket surveillance, even suing to stop it, but the abuses described above are from domestic law enforcement not spooks. If the Google report is anything to go by, those domestic orders are a much bigger problem in terms of sheer numbers (although we do not know the number of FISA requests because Google isn’t even allowed to share it):

- Users targeted in requests by national security letter in 2012: somewhere between 1,000-2,000

- Users targeted in requests by domestic criminal investigators: 31,072

Also, for better or worse, politics is the art of the possible. ECPA reform is possible now; in fact, it’s been ready to go all year save for a single thorny issue about the SEC’s access to data. Bipartisan bills have emerged in both the House and the Senate. The House version now has 142 sponsors, and momentum is growing. So if we can’t muster the political strength to fix the ECPA problem, when a legislative solution is essentially ready to go, there’s zero chance that any real NSA reform will ever pass.

With your help we can fix the law enforcement snooping problem now, and then, with a win under our belt, start chipping away at the big, bad NSA. Sign the whitehouse.gov petition for ECPA reform today!